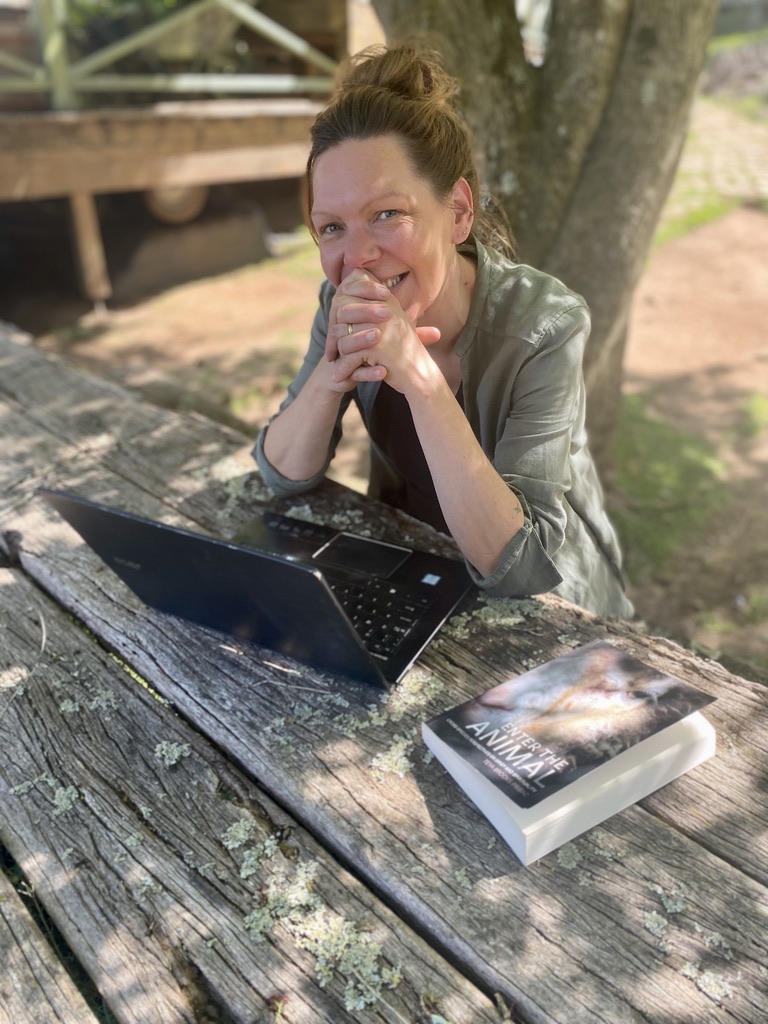

Teya Brooks Pribac and her book Enter the Animal (Lis Bastian)

Story by Lis Bastian

Katoomba artist, writer and scholar Teya Brooks Pribac has spent the last two decades learning about the rich, complex lives and contributions of the animals who are our allies in creating a habitable planet. As part of her animal advocacy she’s written Enter the Animal and Not Just Another Vegan Cookbook. New work on animal cultures is on the horizon.

Key Points:

- Protecting other species is crucial to our existence. Ecosystems cannot reach a steady stable state without wildlife.

- Our dominant Anglo-European narratives see humans as separate from nature and superior to other animals but there are other narratives of connection and interdependence.

- Human grief is the organism’s response to a loss and the same chemical processes are kickstarted in other species too when they experience loss.

Share this article:

Animals have had millions of years to hone evolutionary skills, to become the intelligence that connects and stabilizes physical, chemical and biological worlds through smell, sight, acoustics and many dozens of additional senses, only some of which we possess. Human life on Earth has always been and will continue to be dependent on wildlife because ecosystems cannot reach a steady stable state without them.

“Wildlife in the Balance. Why Animals Are Humanity’s Best Hope.” (Simon Mustoe, 2022)

We now know that protecting other species is crucial to our existence. As we learn more about the extraordinary role each species plays to keep our world in equilibrium, it is becoming clearer just how much we need all the other animals we share our world with. They are our allies in creating a habitable planet.

In the Blue Mountains, for example, each lyrebird ploughs around 350 tonnes of leaf litter and soil every year. According to ‘Wildlife in the Balance’, this keeps the ecosystem intact, absorbs moisture and contributes to cleaning the water we eventually drink. We need lyrebirds to do what they do.

Twenty years ago, Katoomba artist, writer and scholar Teya Brooks Pribac, was, like most of us, unaware of the extraordinarily rich and complex lives and contributions of these allies of ours.

After two decades of research and relationship-building with other species, however, her understanding has deepened.

Teya and sheep (supplied)

Her motivation to start this journey was triggered by concerns about animal suffering, climate change and environmental degradation. She researched the impacts of our diets on the health of the planet. When she read: “you are responsible for what is happening out there because you’re buying the products” she turned vegan overnight.

“I went home and told my partner we’re turning vegan. He panicked, but then we started to learn what to do and I learnt to cook. I started to experiment and I got excited. We shopped in bulk and made everything from scratch: vegan cheese, icecream, everything! It’s much cheaper than buying food pre-prepared and twenty years ago there weren’t many vegan products on the market.”

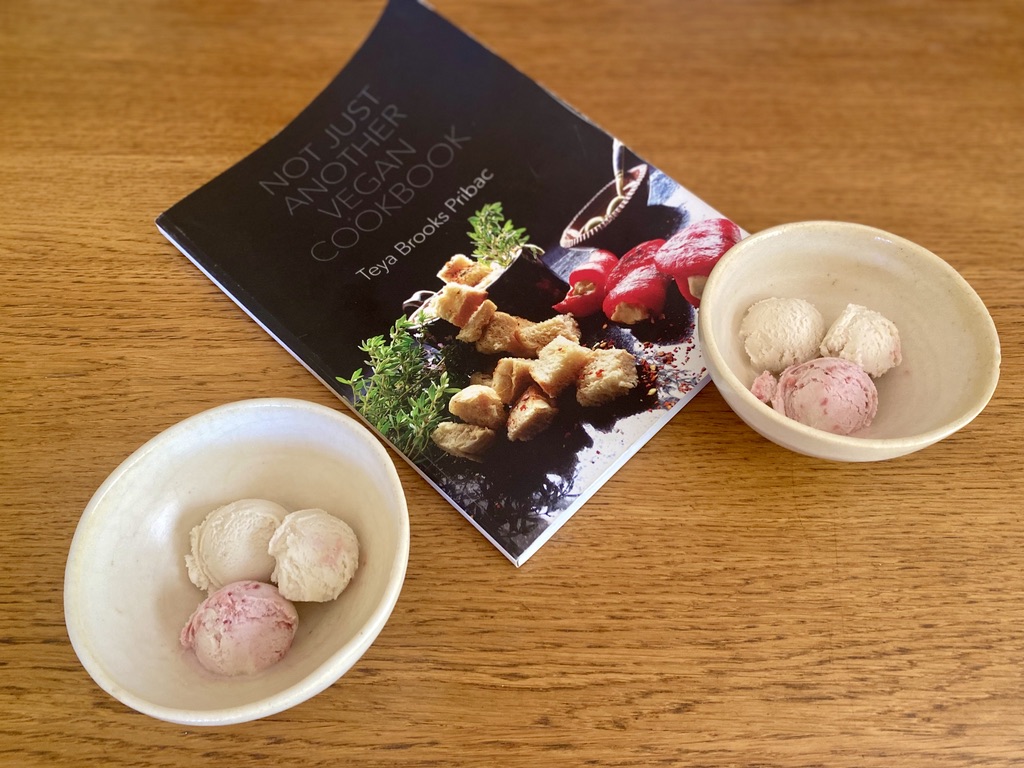

Teya’s food was so well-received by friends that she was encouraged to produce a cookbook. “I enjoyed creating new recipes and taking photos of the food I was producing. Sometimes I’d take 50 pictures of the one dish at different times of day. I learnt from my mistakes and had a lot of fun.” Her Not Just Another Vegan Cookbook was published in 2022 and is now in reprint.

The delicious vegan icecream made by Teya from a recipe in her book (Lis Bastian)

I am visiting Teya on an unseasonably warm spring day in Katoomba and she generously serves me the most delicious vegan lamingtons and icecream she’s made earlier: a testament to her cooking skills.

Vegan lamingtons (Lis Bastian)

In a parallel journey to changing her diet, Teya began learning more about animals and became involved with animal rescue groups and organisations.

“I began to realise how similar we are and how animals are our equals in everything that matters: emotionally, socially. They’re cognitively adapted to different things, but they experience grief like we do. Human grief is the organism’s response to a loss and the same chemical processes are kickstarted in other species too when they experience loss.”

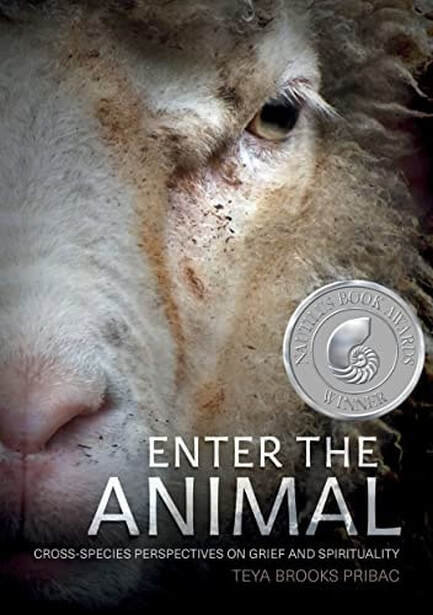

Teya focused her PhD research on grief across species and eventually published the Nautilus award-winning book Enter the Animal.

Teya’s book ‘Enter the Animal’ (supplied)

As a storyteller herself, she believes creative problem solving for the future can be hindered by the stories we accept as a culture.

Her new research is looking for the micro-narratives that have been suppressed by our dominant Anglo-European narratives which see humans as separate from nature and superior to other animals. “This has enabled us to seriously damage the planet and cause a lot of suffering to other animals. But there have been different narratives of connection and interdependence, both in Indigenous and Asian traditions, and throughout western history, from Pythagoras to Leonardo da Vinci to the powerful 19th century vegetarian movement. These vegetarians from the 19th century tended to also be social reformers because they saw the connection between the exploitation of humans and other animals. In Australia they included the founders of Sanitarium (which created Weet Bix) and feminist Henrietta Dugdale, who wrote a utopian novel extolling a vegan lifestyle in 1883 (although the word ‘vegan’ wasn’t coined until 1944).”

“Animals are not biological automatons. We are starting to realise that conservation efforts will really only have a chance to work if we take into consideration animals’ cultures. Animals don’t automatically know what to eat, where to find water, shelter, how to behave. These are things they learn from others. Every bit of the bush is as vibrant with life and culture as your local restaurant strip. I must admit that I hadn’t appreciated this enough until I got myself a macro photographic lens earlier this year and I started to crawl around looking for tiny critters and their interactions.”

Teya photographing dragonflies over her pond (Lis Bastian)

Teya describes observing many of these interactions in the wildlife pond she and her partner have created in their former swimming pool. “The ducks need the water more than we do, so we stopped adding chemicals and added some plants. Last year for the first time we saw a community of snails. There are lots of other bugs, frogs, dragonflies and a copperhead snake. I’ve even been watching a caterpillar mothering her baby … or that’s what it looked like!”

Water snails (Teya Brooks Pribac)

Macrophotography of insects (Teya Brooks Pribac)

There is so much joy in Teya’s voice when she describes this expanded community she is living with: “When you live in this frame of mind it opens up possibilities of community and connection and how to live in a less damaging way.”

Another of the visitors who are part of Teya’s expanded community. (Teya Brooks Pribac)

She also takes care not to leave the track when she goes walking in the bush because she is sensitive to entering the homes of other species. “There are a lot of us and we’re taking up a lot of space. Animals are now becoming nocturnal to avoid us,” she says, and later sends a link to an article in The Conversation: To avoid humans, more wildlife now work the night shift.

Teya’s love for animals is infectious and she talks about the rescue sheep she’s developed a bond with over the years. “You can see how much they love absorbing fresh air, the stars and the smells around them.” With Sharon and Paul Mcley, and their family of 29 woolly sheep in Tasmania, she’s preparing a paper on sheep culture that they’re presenting at a University of Sydney conference in late November.

The one thing that’s very clear is that love and having fun is a common thread through Teya’s life. She started her ‘Magic Detention Project’ about a year ago. “People get used to the place they live in and stop noticing things. I wanted to start paying attention again so I started taking photos of amazing things like clouds, animals, plants. It’s so much fun.”

I leave the interview with the lingering taste of lamingtons and icecream and an increased desire to love and pay attention to everything around me, and, in particular, the many allies I’m sharing this beautiful planet with.

Take Action:

- Try some sample recipes from Not Just Another Vegan Cookbook

- Read Teya’s research here

- Read more about the impact of our diet on the environment

Share this article:

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.