Kowmung, Nattai and Little Rivers. Photo credit: Henry Gold

After focusing on protecting NSW wilderness areas for more than 30 years, conservationist Keith Muir turns his attention to his own Blue Mountains backyard.

Key Points:

- We can’t take this vast wilderness for granted. Without weed control our environment would become much less diverse and unable to offer home to vast numbers of plants and animals. With this habitat loss, species will become regionally extinct or extinct entirely.

- Keith Muir, a former director of Australia’s longest running wilderness organisation The Colong Foundation (now Wilderness Australia), has spent his life protecting large intact natural areas. He now volunteers with the Woody Weed Wanderer Bushcare Group and is involved in campaigns to stop urban weeds entering our bushland.

Share this article:

When I visit Keith Muir’s Katoomba home overlooking lush bushland and creek, I’m keen to talk about his volunteer work for the Woody Weed Wander Bushcare Group.

However, Keith has other plans and steers me away from interviewing him, suggesting better qualified members of the group. Despite being at the forefront of wilderness activism for several decades, he tells me his knowledge of invasive weeds is nowhere near as impressive as theirs.

He may be right, but I’m intrigued to know more about his move from Sydney’s inner west to Katoomba and the motivation that keeps him campaigning.

Keith Muir at home in Katoomba (Liz Durnan)

For those of us who love the Blue Mountains, it’s good to remember that we can’t take this vast wilderness for granted. Whether we enjoy bush walking, climbing, hiking or just staring into the pristine bushland as far as the eye can see, it’s easy to forget that so much of it could easily have been destroyed by various threats.

It’s the driving passion of individuals and their tireless campaign work that has helped save these precious places.

As a director of the Colong Foundation Keith Muir’s work involved ensuring wilderness remained just that.

The Colong Foundation is now known as Wilderness Australia and is Australia’s longest running wilderness conservation organisation. It was founded by Australian conservationist Milo Dunphy, and other activists, in 1968.

Keith fires up when talking about Milo Dunphy, his predecessor at the Foundation and a life-long inspiration.

Milo was the son of Myles Dunphy, an Australian conservationist best known for his work to promote the protection of national parks and wilderness in New South Wales. Milo followed in his father’s footsteps to become a wilderness activist, but was more politically astute, according to Keith.

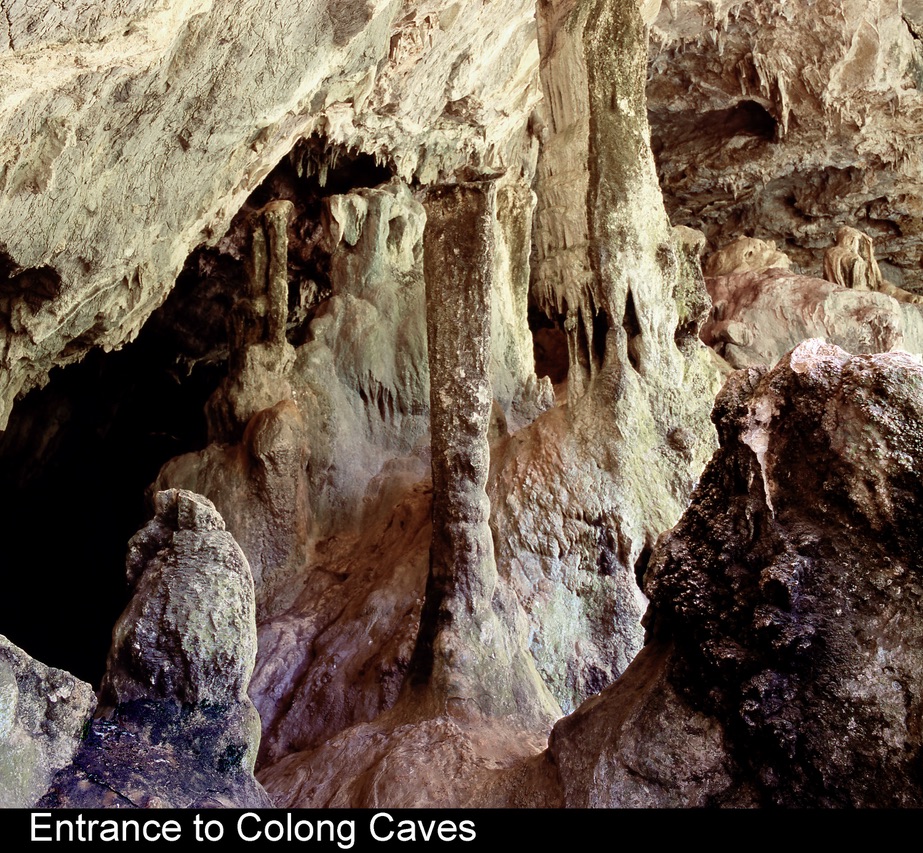

It was Milo who saved areas of the southern Blue Mountains including the Colong Caves: an extensive network of limestone caves. In all, Milo Dunphy’s political leadership saw the NSW National Park estate more than double in area, from two percent to four and a half percent.

Colong Caves. Photo credit: Henry Gold

The Colong Foundation was instrumental in extending the Blue Mountains National Park to cover a huge area, from the Wollondilly River and Kanangra in the south up to the Grose Valley in the north.

During Keith’s time at the Colong Foundation it was extended to include the Nattai National Park, a stunning area of ancient sandstone escarpments, which was the first wilderness to be declared under the Wilderness Act of 1987.

This legislation, says Keith, ensured the saving and continued protection of “many old growth forests along the way.”

Keith is humble but he’s aware of the enormity of what people like Milo, himself, and many others, have achieved at the Colong Foundation. “Large intact natural areas are a vital part of the national park estate. And that’s my life’s work. Trying to protect that,” Keith says.

Mount Colong from Kanangra Tops. Photo credit: Henry Gold

“Now there’s over two million hectares of wilderness in New South Wales,” he says. “Will it survive into the future? I don’t know.”

A reminder, again, we can take nothing for granted.

Does he describe himself as an activist? “That’s one way to describe it. The other is to work to solve the problems presented by protecting a natural area and to assist the government with that solution.”

For a political solution to be effective in the long term it must work for a government from either side of the political spectrum. “You work with both sides of the street,” he says. “If you want to retain national parks, if you want to retain wilderness, world heritage, you name it, you have to work with both.”

Keith hasn’t stopped fighting for large natural areas and has recently achieved some success in the campaign to protect the Gardens of Stone National Park from overdevelopment.

He attributes these conservation successes not to any intellectual talent but to consistency and hard work, working long hours and often on weekends, for much of his career. “It is a little appreciated fact that most people involved in any sort of politics work long hours,” he says.

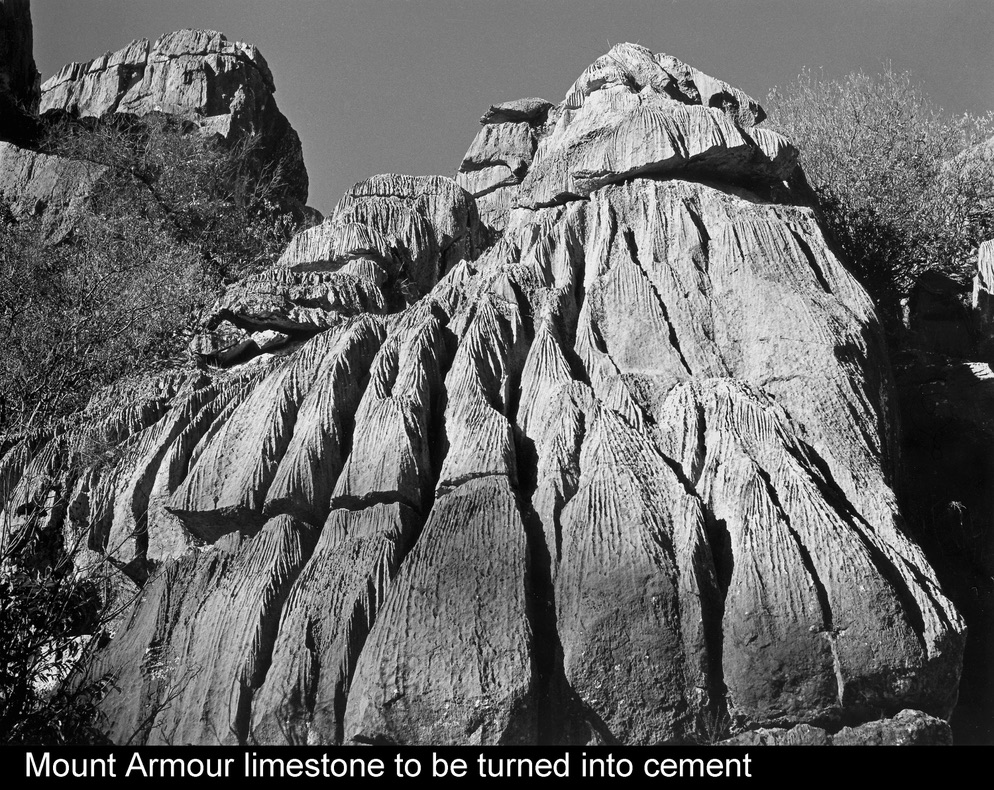

Mount Armour limestone to be turned into cement. Photo Credit: Henry Gold

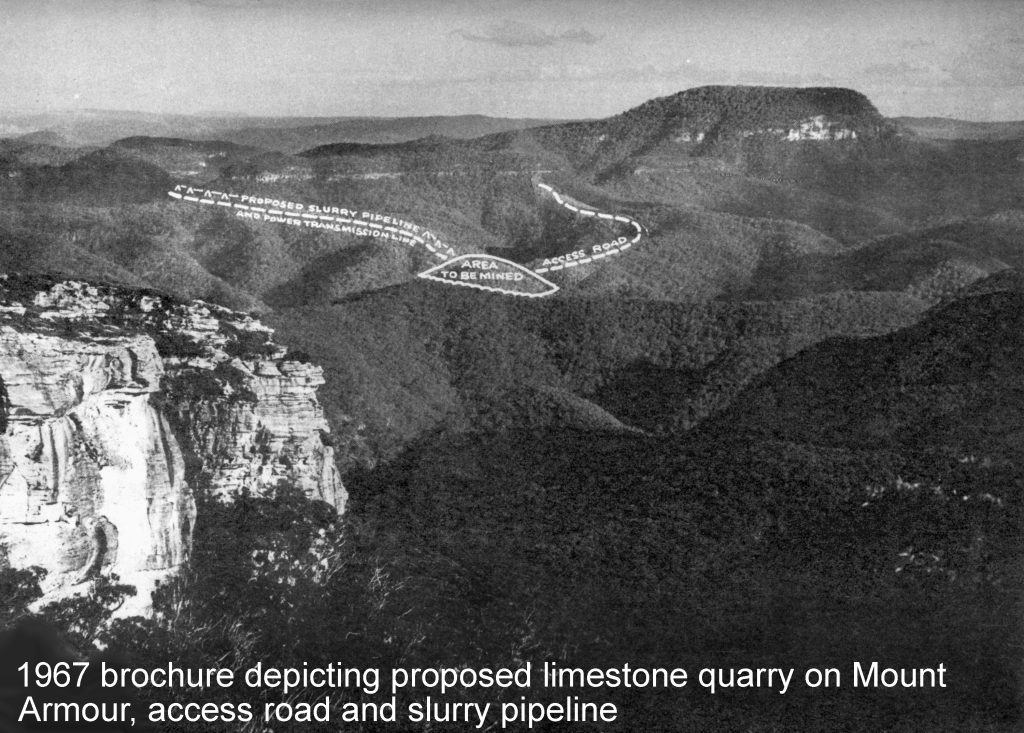

1967 brochure depicting proposed limestone quarry on Mount Armour. Photo Credit: Henry Gold

Keith’s academic background was in natural resource management and before moving into conservation he worked at the Department of Mines and Energy in the Northern Territory.

Now Keith’s focus is closer to home and hands-on, including regular forays into major weeding campaigns locally, as well as the weeds that threaten the creek running through his own block.

Keith turns the Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) acronym on its head and applies it to weed management in the Blue Mountains.

“Everybody complains about NIMBYs. Well, bush regeneration is NIMBY too. Not in my backyard, not in my neighbour’s backyard, out they go!”

The Woody Weed Wander Bushcare group is so named because of the stubborn woody weeds they focus on and that proliferate near his home. He names weeds of concern “proven ecosystem changers” for the damage they inflict on the delicate Blue Mountains ecosystems. They include Himalayan Honeysuckle and Broom.

He’s motivated by the value of bush regeneration but emphasises the ongoing nature of it, with “follow up and constant maintenance” essential to avoid wasting previous efforts.

Keith values an overall holistic approach to weed management for this reason. All the river catchment areas are connected, with the Kedumba Creek leading to the Kedumba River, to the Kedumba Valley and the inner catchment of Warragamba Dam that provides Sydney’s main water supply.

“So, anything here ends up in the World Heritage Area pretty quickly,” he says.

A holistic managed strategy includes identifying goals, assessing what is achievable and what weeds are a priority, identifying target areas and earmarking appropriate resources.

His enthusiasm for the project is infectious but can quickly turn to frustration. While bush regeneration groups are working hard, weeds proliferate in private properties and other government-owned areas, such as along the railway line. If only everyone could be working together, he says, the plan to eradicate weeds could be more effective.

Just as quickly his passion for bush regeneration and the importance of what it can achieve returns. He points out that in other respects the Blue Mountains is lucky: being a sandstone plateau primarily it’s a very low nutrient environment, meaning many weeds don’t like it.

On a personal note, the practical nature of bushcare, not just the goal, brings satisfaction.

“It’s great to just be grounded and pull out weeds, right?” says Keith. “And just forget about everything. You get to mentally switch off and allow yourself to be doing something basic.”

Equally valuable is the learning it brings. “Even when you think you have lots of knowledge,” he says, “you’re always learning from other people who have tremendous knowledge about weeds. You can bring this back to managing your own property.”

The importance of bush regeneration is difficult to overstate, says Keith. Without weed control our environment would become much less diverse and unable to offer home to vast numbers of plants and animals. With this habitat loss, species will become regionally extinct or extinct entirely.

In other words, no weed control would be disastrous. And this is another point Keith likes to make: that we often see disaster only in human terms and how it affects us. But, if we have a planetary, nature-focused view, we look at nature and wildlife as having rights too and we all benefit in the long term.

“That’s why we have national parks,” he says. “That’s why we have world heritage areas. That’s why we have wilderness.

“And we go to those places to engage with nature and to experience thriving mega diverse ecosystems unique to Australia.”

Take Action:

- To become a Bushcare volunteer find a group near you here: http://www.bushcarebluemountains.org.au/groups/

- Read more on the Gardens of Stone campaign: https://www.gardensofstone.org.au/

- Visit wilderness areas: https://www.wildernessencounters.org

Share this article:

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.